Sustainable and safe concepts for climate-friendly shipping

- Project team:

Christoph Kehl (Project management), Reinhard Grünwald, Friedrich Jasper, Christine Milchram

- Thematic area:

- Topic initiative:

Committee on Education, Research and Technology Assessment

- Analytical approach:

TA project

- Startdate:

2022

- Enddate:

2025

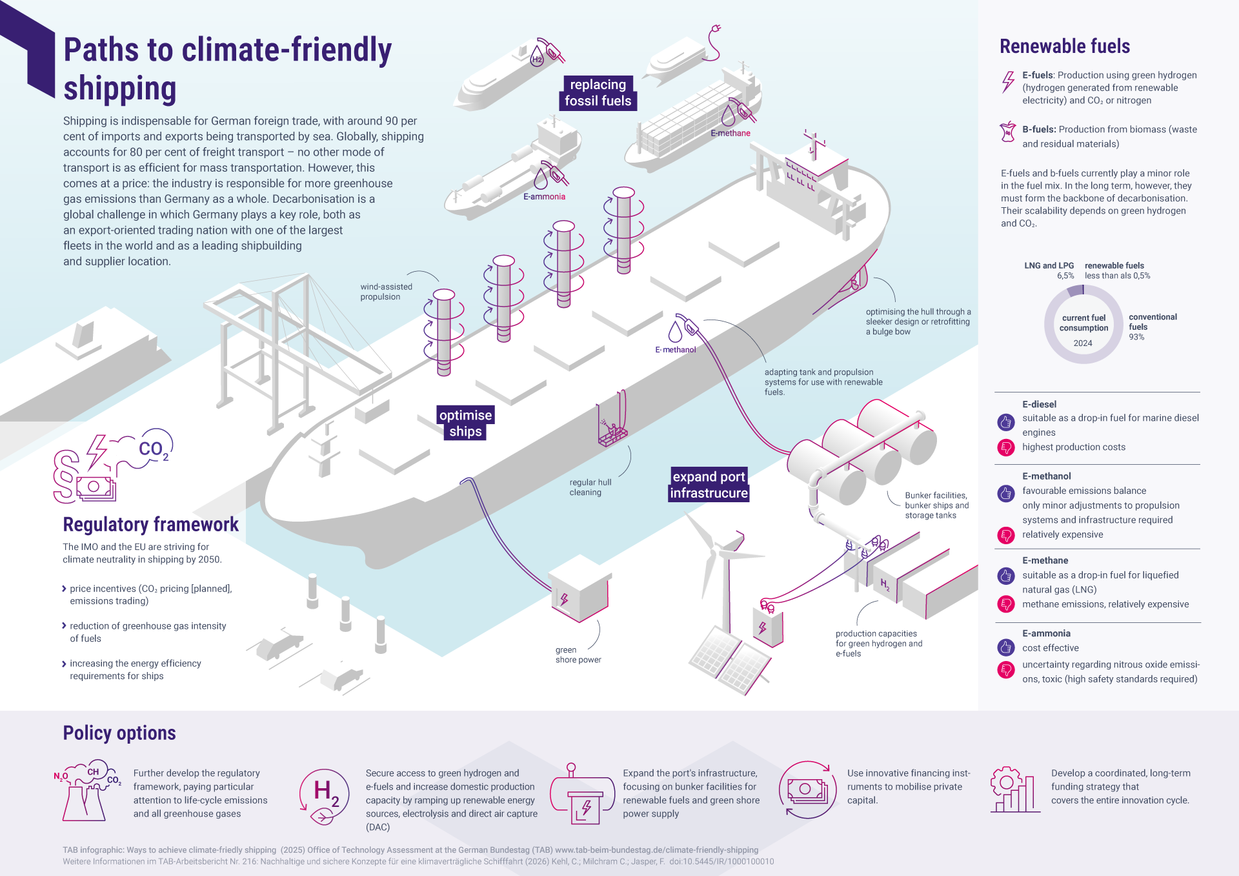

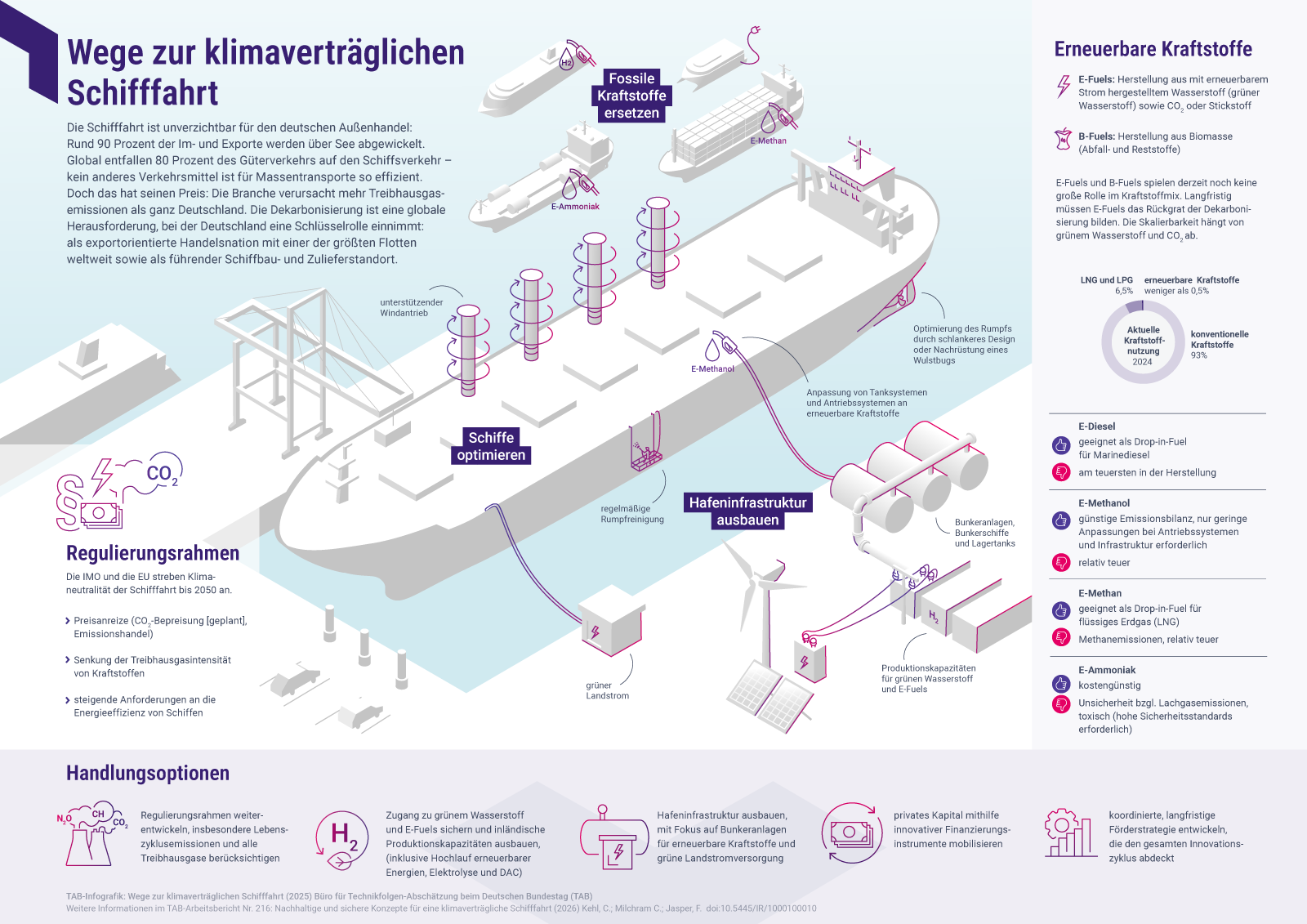

Paths to climate-friendly shipping

At a glance

- Shipping accounts for around 3 % of global greenhouse gas emissions and is one of the most difficult sectors to decarbonise.

- The International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the EU are striving for climate neutrality in shipping by 2050. Regulation is progressing, but there are still relevant gaps.

- Renewable fuels such as e-fuels are a key option for climate compatibility. Their use requires massive investments in production capacities for green hydrogen and maritime infrastructures.

- In addition, increases in efficiency – for example through optimised ship hulls or wind-assisted propulsion systems (WAPS) – are essential in order to reduce fuel consumption.

- The transformation to climate-friendly shipping offers economic opportunities for Germany that can be seized by promoting innovation, expanding infrastructure and participating in international regulatory processes.

sprungmarken_marker_4929

What is involved

Approximately 80 % of global freight transport account for maritime shipping – primarily container ships, bulk carriers and tankers – which are predominantly fuelled by fossil fuels such as heavy fuel oil and marine diesel. Thus, despite its high energy efficiency, shipping accounts for approximately 3 % of global greenhouse gas emissions. If it were a country, shipping would be the fifth largest emitter, ahead of Germany. If the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change are to be achieved, shipping must become more climate-friendly as well.

However, like e. g. aviation, shipping is one of the most difficult sectors to decarbonise. Due to the long transport distances and the high energy demand, direct electrification via battery-electric drives is not viable in most cases. Instead, fossil fuels must be replaced by renewable fuels. The production of these fuels from renewable electricity or biomass, however, involves considerable technical and economic effort. Thus, the use of these fuels is significantly more expensive than using fossil alternatives. This is why additional structural and operational measures must be implemented in order to effectively reduce fuel consumption.

The decarbonisation of shipping is a major challenge – not only from a technical but also from a regulatory perspective. As a global industry, shipping requires climate policy regulations at international level. Given the long service life of ships which ranges from 25 to 30 years, these regulations must also take into account the existing fleet. In view of the large number of players and complex international regulations involved, many decisions are still made too slowly. Currently, many measures required to achieve the climate goals still show considerable deficits.

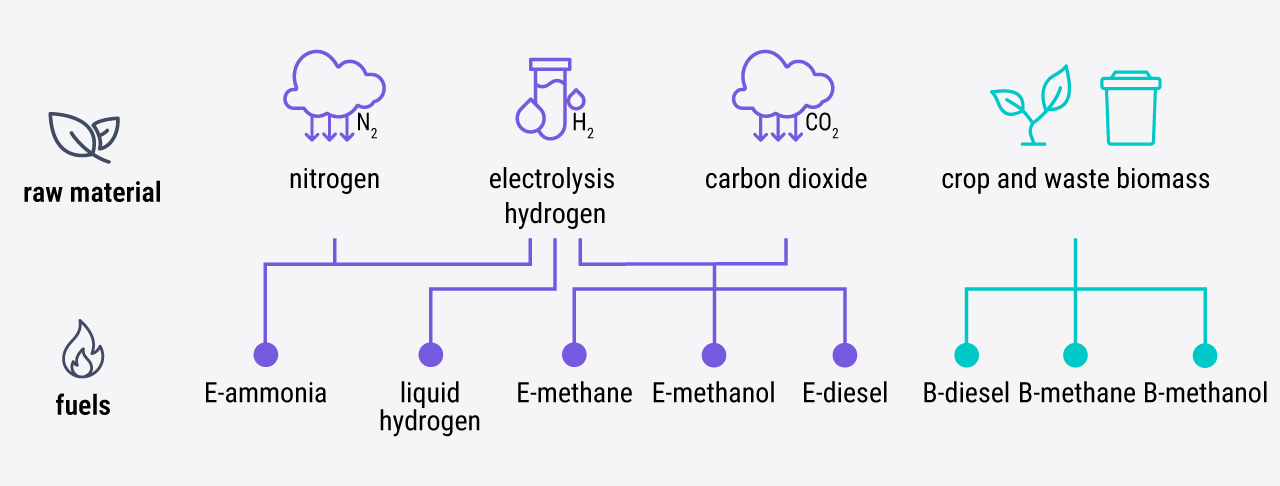

Potentials and challenges of renewable fuels

A key element for climate-friendly shipping is the switch from fossil fuels to renewable fuels, which are either electricity-based as e-fuels or biogenic as b-fuels. E-fuels are produced from hydrogen, which is obtained from water by electrolysis using electricity. Hydrogen can be liquefied and used directly as fuel. Or it can be further processed with carbon dioxide to produce e-diesel, e-methane and e-methanol or with nitrogen to produce e-ammonia. B-fuels are based on biomass and include biodiesel as well as biomethane and biomethanol (Figure 1).

The greenhouse gas emissions of renewable fuels are lower than those of heavy fuel oil and marine diesel: Depending on the type of fuel, between 30 and approximately 100 % of fossil fuel emissions can be avoided. However, the level of emissions varies depending on the production process. Thus, when comparing fuels, the entire life cycle must be taken into account – from production to utilisation on board (well-to-wake emissions). In the case of b-fuels, emissions can only be significantly reduced by producing the fuel from waste and residual materials. In contrast to fuels made from palm, rapeseed or soybean oil, such b-fuels do not cause any emissions due to changes in land use and do not compete with food and animal feed production. However, the global volume of waste and residual materials will not be sufficient to cover the forecast demand for renewable fuels.

Thus, in the long term, the availability of e-fuels is crucial for achieving the climate goals. Here as well, emissions depend on the production method used: Compared to fossil fuels, emissions can only be significantly reduced using green hydrogen which is produced from renewable electricity. Currently, hydrogen comes mainly from fossil sources such as gas extraction. The production of green hydrogen would have to be massively expanded in the years to come. According to current analyses by the International Energy Agency, the electrolysis capacity planned by 2030 will be far from sufficient to meet the demand from shipping (as of October 2024). In addition, the production of e-diesel, e-methane and e-methanol also requires large quantities of carbon dioxide. According to experts, extracting it directly from the air using Direct Air Capture (DAC) is considered to be very important in the long term. However, the technology is not yet sufficiently available.

The question of which fuels will realistically contribute most to climate-friendly shipping not only depends on greenhouse gas emissions – apart from carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide are particularly relevant – but also on their competitiveness compared to fossil fuels. Due to complex production processes and scarce resources, renewable fuels are currently significantly more expensive than heavy fuel oil or marine diesel. Moreover, some fuels require cost-intensive adjustments to ships and infrastructure. And finally, the fuels involve different risks for humans and the environment. This is why special safety regulations are required, some of which still have to be developed.

The comparison of renewable fuels in terms of emissions, economic efficiency and safety risks shows that ammonia and methanol are particularly promising. Ammonia is the cheapest of all renewable fuels to produce, as it does not require carbon dioxide and its production is well established in the chemical industry. However, the considerable environmental and safety risks – some of which are still unresolved – are a disadvantage: On the one hand, nitrous oxide can be released during combustion. This is a highly effective greenhouse gas and its capture from the exhaust gas is associated with additional costs. On the other hand, the high toxicity of ammonia requires particularly strict safety measures. Methanol has a favourable emissions balance, the production costs are in the mid-range of renewable fuels and only relatively minor adjustments to propulsion systems and infrastructure are required. Accordingly, the number of new methanol-powered ships is increasing worldwide. Although liquefied hydrogen presents the best emissions balance, its low energy density means that it requires a lot of storage space and is therefore rather suitable for short distances. The other fuels – renewable diesel and methane – are sometimes less attractive than methanol and ammonia for cost reasons, but act as drop-in fuels due to their similarity to fossil fuels: Methane can be used in existing ships that run on natural gas-based liquefied methane (liquefied natural gas, LNG). E-diesel is likely to be used mainly as an ignition fuel, which is required for hydrogen, methanol and ammonia, or in existing ships fuelled by heavy fuel oil and marine diesel.

Due to the scarce availability of fuels, only very few ships have been powered by renewable energy so far. In order to increase this share in the coming years, production capacities for hydrogen, DAC and e-fuels would have to be expanded. Moreover, the competitiveness of renewable fuels compared to heavy fuel oil and marine diesel would have to be strengthened through instruments such as CO2 prices. Equally important is the development of suitable infrastructures for the delivery and bunkering of fuels as well as the further development of corresponding safety regulations.

Options for efficiency measures

Due to the foreseeable shortage of renewable fuels, it is essential for climate-friendly shipping to make use of any opportunity to increase energy efficiency. The energy demand of ships can be reduced by means of various structural and operational measures, such as optimised hull shapes, lightweight materials, more efficient propellers and rudders, wind-assisted propulsion systems or speed reduction. However, the saving potentials depend on many factors and are therefore difficult to estimate. The feasibility varies depending on the type of ship.

While most structural measures only slightly reduce fuel consumption, a slimmer hull shape with larger main dimensions enables saving potentials of 10 to 20 %. However, this is only feasible for newly built ships. Another promising option is the use of wind-assisted propulsion systems: Retrofittable wind-assisted propulsion systems such as rotor sails can reduce the energy demand by up to 15 %. Wind-based main propulsion systems will offer even greater potential in the long term, but currently are hardly technically feasible for merchant ships. Both wind propulsion concepts require free deck space. This is why they are primarily suitable for tankers and, to some extent, for bulk carriers.

In terms of operational measures, reduced speed and regular cleaning of the hull and propeller have a particularly positive effect on energy consumption – with potential savings in the double-digit percentage range in each case. However, it should be noted that effective measures such as speed reduction or optimised hull shapes might reduce transport capacity, which might require the use of additional ships. In addition, the percentages saved by individual measures cannot simply be added together, as there are interactions between them.

This is why, in the case of newly built ships, energy aspects should be fully taken into account already in the design phase. Although retrofitting is often more expensive and less efficient, it is nevertheless crucial for decarbonisation due to the long service life of ships (approx. 25 to 30 years). A large part of the savings potential can be tapped making use of existing expertise. However, further technological innovations – for example with regard to wind propulsion – are necessary and require a strong shipbuilding industry. Here, Germany is in a strong position: The German maritime supply industry is one of the leading international providers and supplies key components such as optimised rudders, propellers and rotor sails for more energy-efficient shipping.

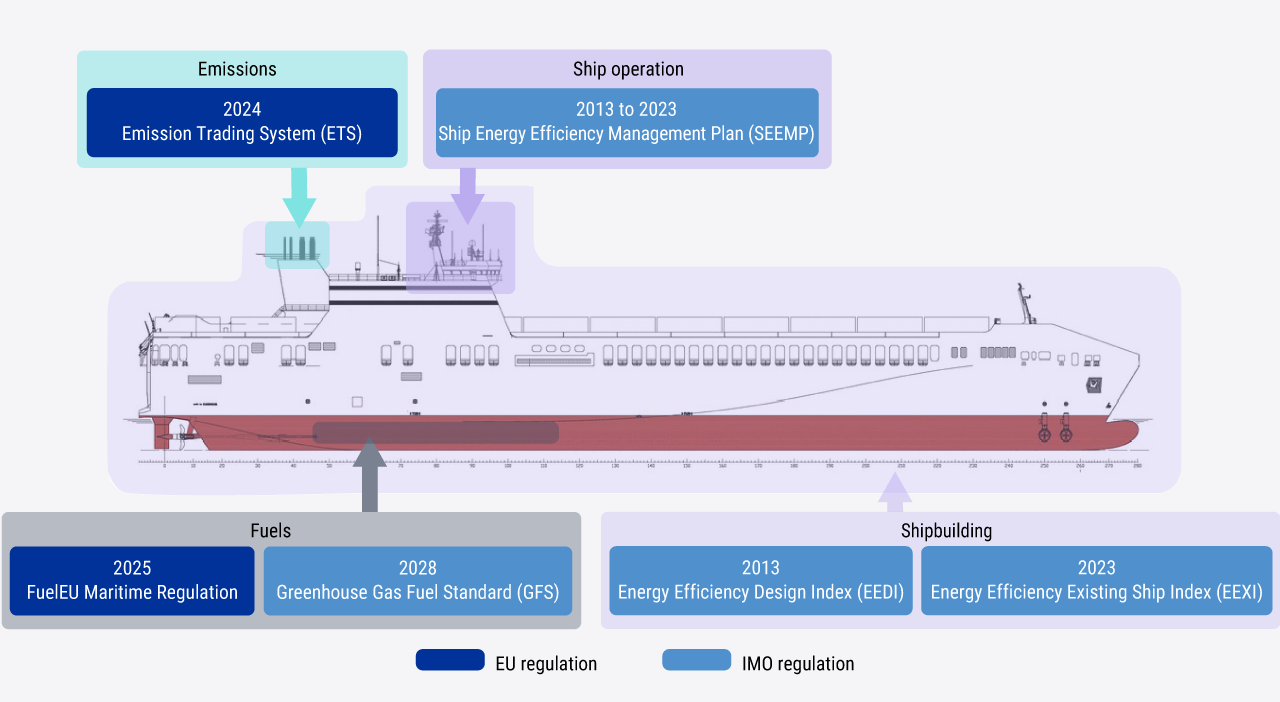

Regulatory framework

Until 2018, maritime shipping was largely exempt from international climate commitments. The Paris Agreement on climate change now also applies to maritime shipping, with the aim of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. The central regulatory body is the International Maritime Organization (IMO) of the United Nations. Its regulations are binding for all member states worldwide and apply to different levers: The Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) requires shipowners to draw up operational plans in order to reduce energy consumption in compliance with IMO requirements, while the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) and the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) continuously define stricter efficiency limits with regard to technical design for new and existing ships. Moreover, with the Greenhouse Gas Fuel Standard (GFS, entry into force in 2028), the IMO is preparing a global CO2 pricing system for the first time, which is intended to gradually reduce the greenhouse gas intensity of marine fuels.

The European Union also has a significant influence on the regulation of shipping (Figure 2): The FuelEU Maritime Regulation, which has been in force since 2025, stipulates upper limits for the greenhouse gas intensity of the energy consumed on board in order to promote the use of renewable and low-carbon fuels. Moreover, shipping has also been part of the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) since 2024. This applies to ships with a gross tonnage (GT) of 5,000 or more, regardless of the flag they fly, as soon as they call at EU ports.

Nevertheless, there are still weaknesses in the regulatory framework. Many measures only cover the instantaneous emissions on board and neglect emissions from the upstream chain. In addition, the measures of the IMO – apart from the GFS – focus almost exclusively on CO2, while other climate-impacting gases such as methane and nitrous oxide, which might arise from alternative fuels, are often not taken into account. Thus, incentives arise that might result in decisions leading to undesirable developments.

There are synergies and conflicts between the EU and IMO measures for climate protection in maritime shipping due to different responsibilities and scopes. This involves the risk of inefficient double regulation. Thus, close coordination between the EU and the IMO is essential for effective climate protection in international shipping.

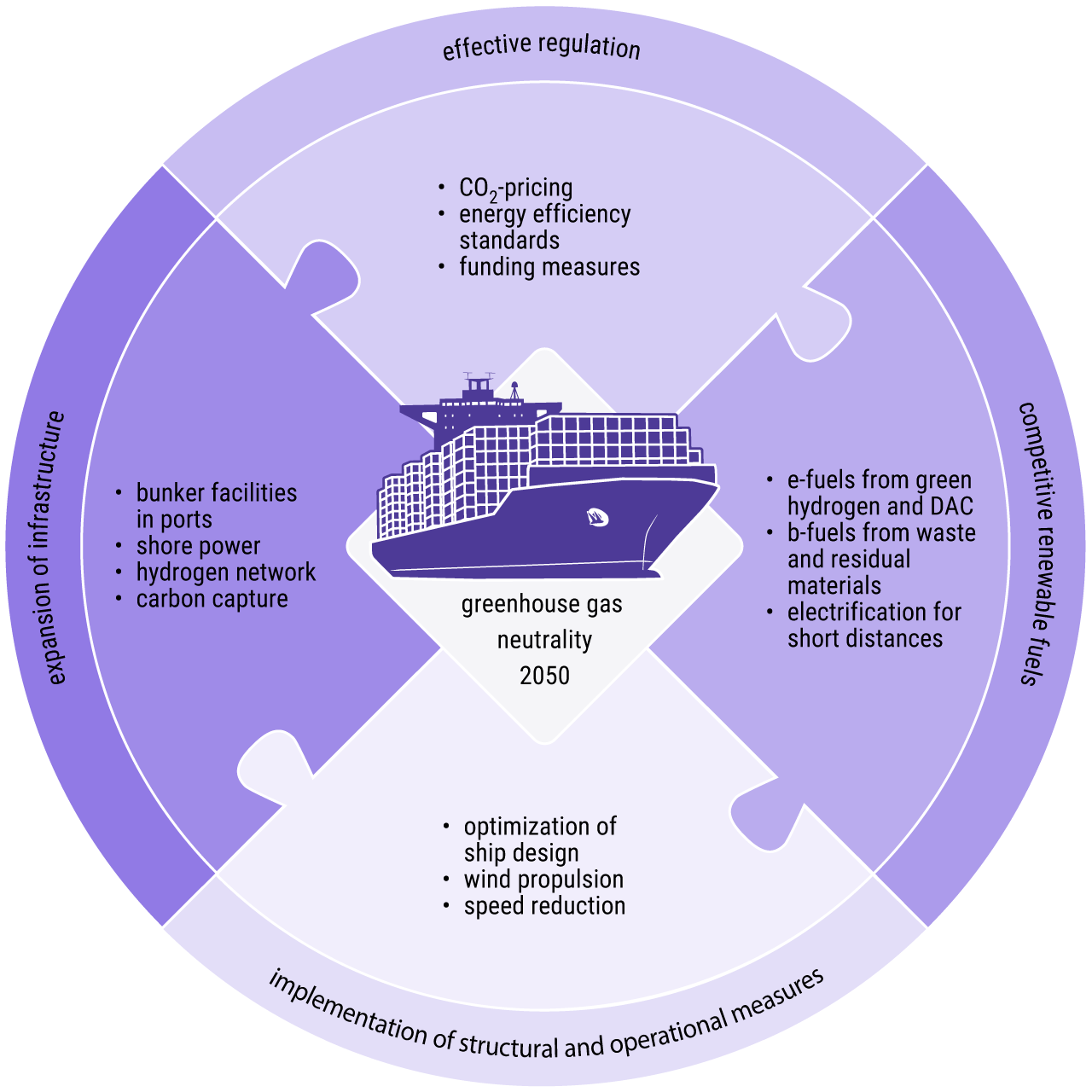

Options for action for German politics

The successful decarbonisation of shipping by 2050 is based on three key prerequisites: sufficient production capacities for e-fuels, the expansion of maritime infrastructure (especially in ports) as well as reliable and ambitious regulation. Germany is one of the leading maritime nations and can play a decisive role in shaping all relevant fields.

To achieve greater independence from energy imports, it makes sense to build up domestic production capacities for green hydrogen and e-fuels. Industrial production is still in its infancy and requires the continuous integration of renewable power generation, water and CO2 supply (e. g. via DAC) as well as advanced synthesis processes. As the electricity demand for e-fuels is enormous, an accelerated expansion of renewable energies is indispensable. There are also technological bottlenecks with regard to hydrogen electrolysis, as these processes still need to be scaled up and further developed. DAC in particular plays a key role in large-scale industrial e-fuel production. An industrial ramp-up requires improved processes, comprehensive demonstration projects and significant cost reductions. Currently, planned production plants for e-fuels worldwide would only cover a fraction of the demand in Germany. Thus, availability is a key challenge.

At the same time, fundamental infrastructure measures are needed in German ports. The German government's National Ports Strategy provides for modernisation – for example, the expansion of bunkering facilities for renewable fuels and the supply of green shore power to reduce emissions and charge battery-electric ships. The shore power obligation decided at EU level in 2023, which will come into force in 2030, is increasing the pressure on port operators to create the necessary infrastructure. This requires considerable investment, which must be supported by targeted funding programmes.

The total investment required for complete decarbonisation is very high. Innovative financing tools, such as so-called ‘blue bonds”, can mobilise private capital. At the same time, opportunities are emerging for maritime industry to position itself in the growth market for alternative drives and efficiency technologies. However, long development cycles and uncertain sales markets are currently bearing certain investment risks. This is why reliable framework conditions, long-term funding programmes and clear targets are required in order to ensure security of planning and investment.

Measures on the path to achieving greenhouse gas neutrality

Downloads

|

TAB-Fokus no. 50 Sustainable and safe concepts for climate-friendly shipping (PDF) The policy brief TAB-Fokus offers a compact overview of the content and results of our TA analyses on four pages. |

|

|

|

TAB-Arbeitsbericht Nr. 216 (in German only) Nachhaltige und sichere Konzepte für eine klimaverträgliche Schifffahrt (PDF) The full working report examines the key technological developments, infrastructure requirements and regulatory instruments necessary for achieving largely climate-neutral shipping by 2050. The report analyses technical maturity levels, systemic interactions, and the necessary political and economic framework conditions. It also discusses technical, ecological, and regulatory limitations. |

||

|

TAB Infographic Wege Paths to climate-friendly shipping (PDF) The infographic visualises the most important findings and policy options on one page, |

In the Bundestag

The final report on the TA project was approved by the Committee on Research, Technology, Space and Technology Assessment on 28 January 2026, after which it was incorporated into parliamentary work.

Procedure - Report on the Parliament server (DIP)

Technikfolgenabschätzung (TA) Nachhaltige und sichere Konzepte für eine klimaverträgliche Schifffahrt

In the media

- swr.de (09.02.2026), Wie kann der Schiffsverkehr klimafreundlicher werden?

- taz.de (06.02.2026), Klimaschädlicher Seehandel: Technologieoffene Tanker fahren nicht auf Klima-Kurs.

- background.tagesspiegel.de (+) (06.02.2026), TAB-Bericht für den Bundestag: Wie die maritime Branche klimaneutral werden soll

- sciencemediacenter.de (06.02.2026), TAB-Bericht: Wie wird die Schifffahrt klimafreundlich?

Previous publication on the topic

|

Themenkurzprofil Nr. 57 (in German only) Innovative Schiffbaukonzepte: Beitrag zur Nachhaltigkeit |